Introduction: Nigeria’s Energy Deficit and the Case for Small Hydropower

Nigeria holds the world’s largest electricity access deficit, with over 85 million people and about 43 percent of its population lacking grid-connected power (World Bank). This persistent shortfall constrains industrial growth, deters foreign investment, weakens essential services such as healthcare and education, and costs the economy an estimated $26.2 billion annually, nearly 2 percent of GDP. While the nation’s installed generation capacity is approximately 13,000 MW, transmission constraints and underinvestment mean that less than 5,000 MW reaches end-users, leaving reliable electricity available to only 13 percent of Nigerians.

Access to electricity is also deeply unequal. Urban areas record access rates of around 84 percent, compared to only 26 percent in rural areas, with rural residents, low-income households, and those with limited education most likely to be excluded (Afrobarometer). Among those connected, just 18 percent enjoy electricity that works most or all the time. As a result, millions of households and businesses rely on petrol and diesel generators, driving up energy costs, greenhouse gas emissions, and air pollution. This dependence on fossil-fuel backup systems worsens climate risks, as noted by the Director of Health of Mother Earth Foundation, which links generator emissions directly to climate change and public health concerns.

Expanding renewable energy presents a viable pathway to bridge Nigeria’s electricity gap while advancing the country’s climate goals (IRENA). The nation is endowed with abundant solar, biomass, and hydropower resources, yet less than 30 percent of each is harnessed. Hydropower alone offers an estimated 15,000 MW potential, including 3,500 MW from small hydropower (SHP), but only a fraction has been developed, with over 70 micro dams, 126 mini dams, and 86 small hydropower sites identified nationwide.

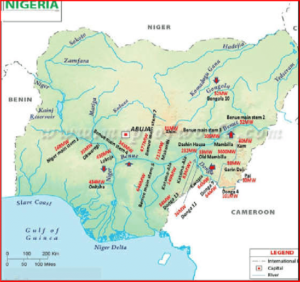

The map below illustrates the spatial distribution of Nigeria’s small and large hydropower resources, highlighting key river basins and identified project sites across the country.

Figure 1: Nigeria’s map showing small and large hydropower sites

However, the development of large-scale hydropower plants such as Kainji and Jebba has revealed major limitations. Studies highlight that these dams have caused extensive flooding, sedimentation, and habitat disruption within surrounding communities. For instance, sediment accumulation and flooding along the River Niger basin have led to widespread environmental degradation and the displacement of thousands of residents. The high risk of dam failure and the recurring need for emergency preparedness plans further underscore their vulnerability. Beyond the environmental and social costs, the financial burden of maintaining such large dams remains considerable. Rehabilitation and environmental management efforts alone run into millions of dollars, while their generation capacity often falls below installed levels due to equipment deterioration and sediment blockage.

These drawbacks have reinforced the attractiveness of Run-of-River (ROR) hydropower systems. Unlike conventional dams, ROR systems utilize the natural river flow-up to 95 percent of the mean annual discharge, without large reservoirs or extensive land submersion. The diverted flow passes through a penstock or tunnel to drive turbines before being returned downstream. This minimizes sediment buildup, flooding, and displacement, while significantly reducing construction and maintenance costs. ROR hydropower is thus widely regarded as an environmentally friendly or “green” technology, capable of supplying reliable electricity to small communities without the ecological disruptions associated with traditional hydropower.

An Overview of the Run of River Hydropower and Its Significance

Run-of-River (ROR) hydropower is a system within the broader category of small hydropower (SHP). SHP generally refers to projects with capacities up to 10 MW and includes various scales such as pico (<10 kW), micro (<100 kW), mini (<1 MW), run-of-river, storage, and hybrid systems, all of which harness the kinetic energy of flowing water through turbines to generate electricity or mechanical power (IEA; Kothari; Yin et al.). ROR stands out for its damless design and minimal impoundment, maintaining the river’s natural flow regime and ecological balance. Typically, the system diverts part of the river flow through a low dam or weir into a penstock that channels pressurized water to turbines housed in a powerhouse. The turbines rotate a generator to convert kinetic energy into electricity, after which the water is safely returned downstream via a tailrace (Renewable Energy UK).

The main components of ROR hydropower include the weir, intake, canal, sand trap, forebay, penstock, powerhouse, tailrace, poles, and desilting tanks. These components work together to maintain consistent flow, regulate pressure, and prevent sediment accumulation. This integrated design allows ROR plants to operate with minimal maintenance, long lifespans of up to 80 years, and reliable generation in steep, fast-flowing rivers while preserving aquatic ecosystems (EUSUSTEL; Pollution Probe). Internationally, ROR technology has gained significant traction across both developed and developing regions. Leading hydropower nations such as China, Brazil, and Canada, already home to some of the world’s largest dam projects, are increasingly deploying ROR systems as part of their low-carbon transition strategies. Likewise, countries with mountainous terrains such as Austria, Switzerland, Norway, and Nepal have widely adopted ROR technology, leveraging their natural topography and river gradients to enhance technical feasibility and cost-effectiveness.

This image illustrates a run-of-river (ROR) hydropower system, showcasing components like the weir that diverts the river flows to generate clean electricity with minimal environmental impact.

Figure 2: The ROR hydropower showing the various components of the system

ROR hydropower is particularly suitable for rural and off-grid electrification due to its scalability, low life-cycle costs, and limited environmental disruption. Power potential is determined using the equation

P = Q × H × 7.83 (where P represents power in kilowatts (KW), Q is the flow rate in cubic meters per second (m³/s), and H is the head in meters (BCSEA)). Although reduced flow and habitat fragmentation remain potential environmental considerations, appropriate engineering interventions such as fish ladders and sediment management can effectively mitigate these challenges (Pollution Probe; IEA).

Despite challenges in financing, regulation, and grid integration (Kelly-Richards and Ali et al), ROR technology remains a proven and adaptable approach for clean energy generation. Its successful adoption across diverse geographies demonstrates its potential to address Nigeria’s persistent energy deficit through the sustainable use of its underutilized river systems (Olatunde, 2020).

Potential Sites and Geographical Suitability of ROR in Nigeria.

Nigeria’s diverse river systems and existing water infrastructure create a favorable landscape for the development of Run-of-River (RoR) hydropower. Several multipurpose dams, such as Challawa Gorge in Kano State, Ikere Gorge in Oyo State, and Doma Dam in Nasarawa State, illustrate significant retrofit potential. The Challawa Gorge Dam, with a reservoir capacity of about 1.2 billion cubic meters, currently serves irrigation and water supply needs but could host small to medium RoR units capable of generating several megawatts without major structural alterations. Similarly, Ikere Gorge Dam on the Ogun River, with a reservoir volume of approximately 690 million cubic meters, was initially intended for a 37.5 MW hydroelectric facility but remains largely underutilized. Doma Dam, though smaller in scale, could support low-head micro- to mini-hydro systems suitable for localized power supply.

Beyond these existing structures, multiple river stretches present favorable hydrological profiles for RoR development. Sections of the Niger, Benue, Kaduna, Gongola, Cross River, and Ogun rivers exhibit sufficient flow rates and head gradients to support low-head turbine technologies such as Kaplan and crossflow systems, which are designed for variable discharge conditions. Some of these sites, particularly in the middle and northern river basins, are also proximate to rural demand centers, offering decentralized energy solutions that minimize transmission losses and stimulate productive end uses such as agro-processing.

Preliminary hydrological modelling indicates that these sites could integrate Dynamic Water-Level Regulation (DWLR) systems to optimize seasonal flow variations while safeguarding aquatic ecosystems. However, site-specific feasibility studies, incorporating flow-duration analysis, sediment load assessment, and stakeholder engagement, will be critical in determining technical and economic viability.

While the geographical and infrastructural foundations are promising, their translation into operational projects will depend on addressing the technical, financial, and institutional barriers outlined in the next section.

Barriers to Run-of-River hydropower Development in Nigeria

Despite its significant potential, the development of run-of-river (RoR) systems, in Nigeria is impeded by a combination of technical, regulatory, financial, environmental, and socio-economic barriers. These constraints must be systematically addressed to harness Run-of-river as a reliable and sustainable component of Nigeria’s energy mix.

-

Technical Barriers

The technical feasibility of ROR projects is site-specific and depends on accurate assessments of hydrological conditions such as flow rate and head. In Nigeria, limited and outdated hydrological data, especially for remote regions, hinders optimal site selection (Igweonu & Joshua). Grid integration also poses a major challenge, as most RoR installations are located in off-grid or underserved rural areas with weak or non-existent transmission infrastructure.

Additionally, there is limited availability of advanced turbine technologies suited for low-flow, low-head environments common in Nigeria. Access to modern, modular turbines that can efficiently operate under variable flow conditions remains limited. The lack of local manufacturing capacity and skilled technical personnel further compounds the operational and maintenance challenges.

-

Regulatory and Policy Constraints

The regulatory framework governing ROR projects in Nigeria remains fragmented and often inconsistent across government institutions. Licensing and permitting processes are complex, time-consuming, and lack transparency, thereby increasing transaction costs and deterring private sector involvement (Atoyebi & Isaac).

Frequent changes in tariff structures and unclear incentives create policy uncertainty. Moreover, the absence of streamlined frameworks for accessing land and rights-of-way, especially in regions with traditional or communal land ownership, leads to delays and community disputes (Idiaghe, Umar).

-

Financial and Investment Challenges

Run of River projects are capital-intensive and require substantial upfront investments, often with long payback periods. Access to affordable and long-term financing remains limited. Many local developers lack the collateral, credit history, or bankable project documentation to secure loans. Furthermore, project bankability is affected by uncertainties around tariff regimes, revenue collection mechanisms, and payment reliability, especially in rural off-taker arrangements.

Currency risk also plays a role, as many SHP components are imported, and local financiers are reluctant to fund infrastructure in foreign currency. The lack of risk mitigation instruments, credit guarantees, and public-private investment platforms has restricted investor confidence in SHP and RoR development in Nigeria (Adelaja).

-

Environmental and Social Considerations

Although ROR is often considered environmentally benign compared to large hydropower, it can still generate ecological and social disruptions if poorly planned. RoR systems can alter riverine ecosystems by changing flow regimes, obstructing fish migration, and affecting sediment transport. Improperly designed diversion structures can lower downstream water availability, affecting agriculture and aquatic biodiversity (Renewable Energy UK).

To mitigate these impacts, environmental best practices such as fish ladders, desilting structures, and habitat restoration must be integrated into project design. Regulatory enforcement of Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) and compliance monitoring also remains weak.

Socially, SHP projects may interfere with traditional land use and livelihoods. Without early and inclusive stakeholder engagement, projects may face resistance from host communities. Issues around equitable benefit-sharing, cultural heritage preservation, and fair compensation remain unresolved in many project contexts.

-

Infrastructure and Grid Integration

Another key constraint is the limited availability of supporting infrastructure such as roads, transmission lines, and substations, especially in rural and remote areas where RoR plants are most viable. Without strategic planning for grid expansion or standalone microgrids, SHP projects may remain isolated and underutilized.

Even in cases where grid connectivity is possible, the unreliability of Nigeria’s national grid discourages interconnection, particularly when tariff incentives for distributed generation remain weak or inconsistent.

Addressing these multifaceted barriers requires a holistic, multi-stakeholder approach that aligns policy, finance, technology, and community participation. Clear and stable regulatory frameworks, robust technical assessments, financial de-risking tools, and inclusive environmental and social safeguards are all necessary to accelerate SHP deployment.

The Way Forward: Unlocking the Potential of Small Hydropower and Run-of-River Systems in Nigeria

To fully realize the transformative potential of run-of-river (RoR) technologies in Nigeria, a multifaceted and strategic approach is required, one that aligns institutional support, financing mechanisms, technological innovation, and community participation.

-

Strengthening Policy and Regulatory Frameworks

The development of ROR in Nigeria hinges on the establishment of a stable, transparent, and investor-friendly regulatory environment. Clear licensing procedures, competitive and cost-reflective tariff structures, and harmonized inter-agency coordination are critical to reducing bureaucratic bottlenecks. A streamlined policy framework would not only reduce investor risk but also foster long-term confidence in the ROR sector.

Incentivizing ROR development through fiscal policies such as tax waivers on equipment imports, concessional financing, and performance-based subsidies can further stimulate private sector participation (Sani & Sambo).

-

Enhancing Access to Finance and Investment

High upfront capital costs and perceived investment risks remain significant barriers to ROR deployment. Expanding access to concessional finance, credit guarantees, and blended financing structures is essential to improve project bankability. International financial institutions such as the World Bank, African Development Bank (AfDB), and International Finance Corporation (IFC) can play a catalytic role by providing concessional loans, grants, and risk-sharing mechanisms.

Furthermore, integrating ROR projects into climate finance frameworks such as the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) or Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) can open new revenue streams through the sale of carbon credits. These mechanisms align well with Nigeria’s climate commitments and can attract climate-aligned capital.

-

Leveraging International Partnerships and Technical Expertise

Collaborating with international organizations, donor agencies, and technical institutions can accelerate ROR adoption by transferring knowledge, technologies, and global best practices. Platforms such as IRENA, UNIDO, and the International Hydropower Association (IHA) offer valuable support in the areas of project design, grid integration, environmental safeguards, and lifecycle cost optimization.

Bilateral and multilateral partnerships should be pursued to facilitate peer learning, technical assistance, and co-financing arrangements that reduce both operational and financial risk.

-

Promoting Community Participation and Local Ownership

Sustainable ROR implementation must be anchored in community engagement and inclusive development. Empowering local populations through participatory planning processes enhances project legitimacy and ensures alignment with local development priorities.

Establishing community-based ownership models, where local stakeholders have equity or governance roles in ROR projects, fosters accountability, long-term maintenance, and social buy-in. Moreover, training programs aimed at building local technical and managerial capacity not only enhance operational sustainability but also generate employment and stimulate rural economies.

Respect for cultural heritage and early resolution of land tenure and usage conflicts are essential to building trust and ensuring social acceptance. Inclusive benefit-sharing models such as local electrification, irrigation schemes, or revenue-sharing agreements should be institutionalized as part of project development.

-

Integrating ROR into National Electrification Strategy

The integration of RoR systems into Nigeria’s broader electrification and energy transition strategy is essential for achieving Sustainable Development Goal 7 (access to affordable, reliable, sustainable energy for all). ROR should be prioritized within decentralized energy frameworks, especially for rural and peri-urban communities where grid extension is economically unviable.

A national ROR roadmap, backed by comprehensive resource mapping, pipeline development support, and standardized project documentation, would significantly improve coordination and deployment.

In conclusion,

Nigeria’s energy access challenge, marked by over 85 million people without grid electricity and only 13% enjoying a reliable supply, continues to constrain development and climate goals. The overreliance on diesel generators and a fragile grid highlights the urgency for clean, distributed alternatives.

Run-of-River systems offer a scalable and low-carbon solution well suited to Nigeria’s river networks. With 3,500 MW of untapped SHP potential, it presents a viable path to rural electrification and decentralized power.

However, barriers remain, ranging from regulatory gaps and limited hydrological data to financing and community engagement. Addressing these will require policy reform, international collaboration, and inclusive project models.

To realize Run of River hydro power’s full potential, Nigeria must embed it into national electrification and climate strategies, strengthen enabling frameworks, and empower local ownership. With coordinated action, Run of River Hydro Power can become a cornerstone of Nigeria’s energy transition.